Gardom's Edge: in Search of a Neolithic Plastic Rock

Gardom’s Edge, a gritstone escarpment that overlooks Baslow, is both very beautiful and largely ignored. It’s not particularly high, at 275 feet, and not only are there no National Trust trails that take you through the important sites here (maybe deliberately; maybe not), but the OS doesn’t illustrate any footpath at all. Even from the A621 that runs below, the outcrops are hidden by trees, perhaps explaining why its many rocky routes aren’t more popular with climbers; they flock instead to Birchen Edge, across the plateau to the East.

On Birchen Edge, there are sign posts, steep steps and well worn paths that lead you up to its late-Georgian monuments. The Neolithic and early Bronze Age remnants on Gardom’s Edge are unmarked. It’s up to you to find them.

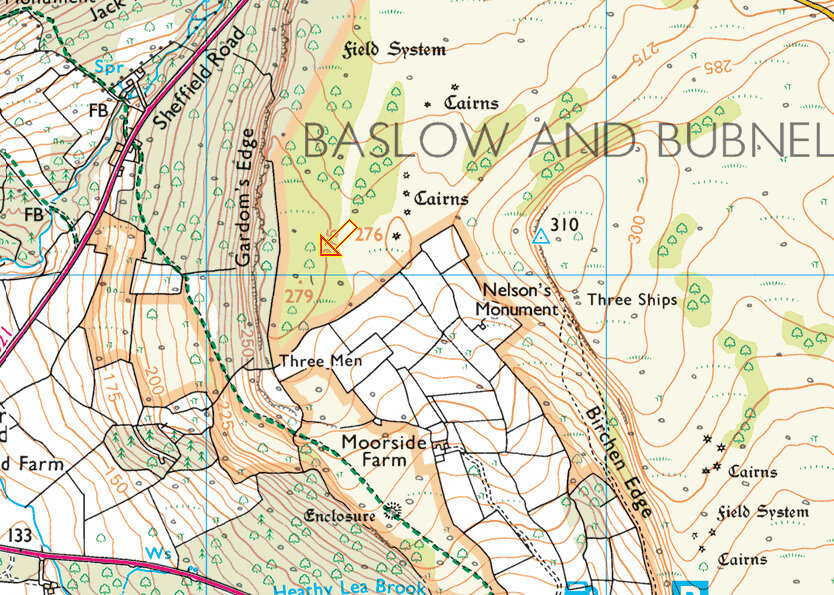

The OS Map shows Gardom’s Edge and Birchen Edge and the plateau between them. The arrow points to the location of the replica carved rock.

The Route

If you approach Gardom’s Edge from the gate on Clodhall Lane (close to the intersection with the A621), there doesn’t look to be much of interest ahead of you: to the left, Birchen Edge begins to rise up, but everything else is boggy moorland. In January, when I went twice, the long dead grass gave it the decidedly un-Peak-like appearance of the savannah.

When you take the worn path that bears right, slowly inclining, the tone of the landscape begins to shift. Ignore the fencing and the first stiles or gates to your right and keep straight on: you want the entrance that lets you cross from barren moor into a lush birch woodland.

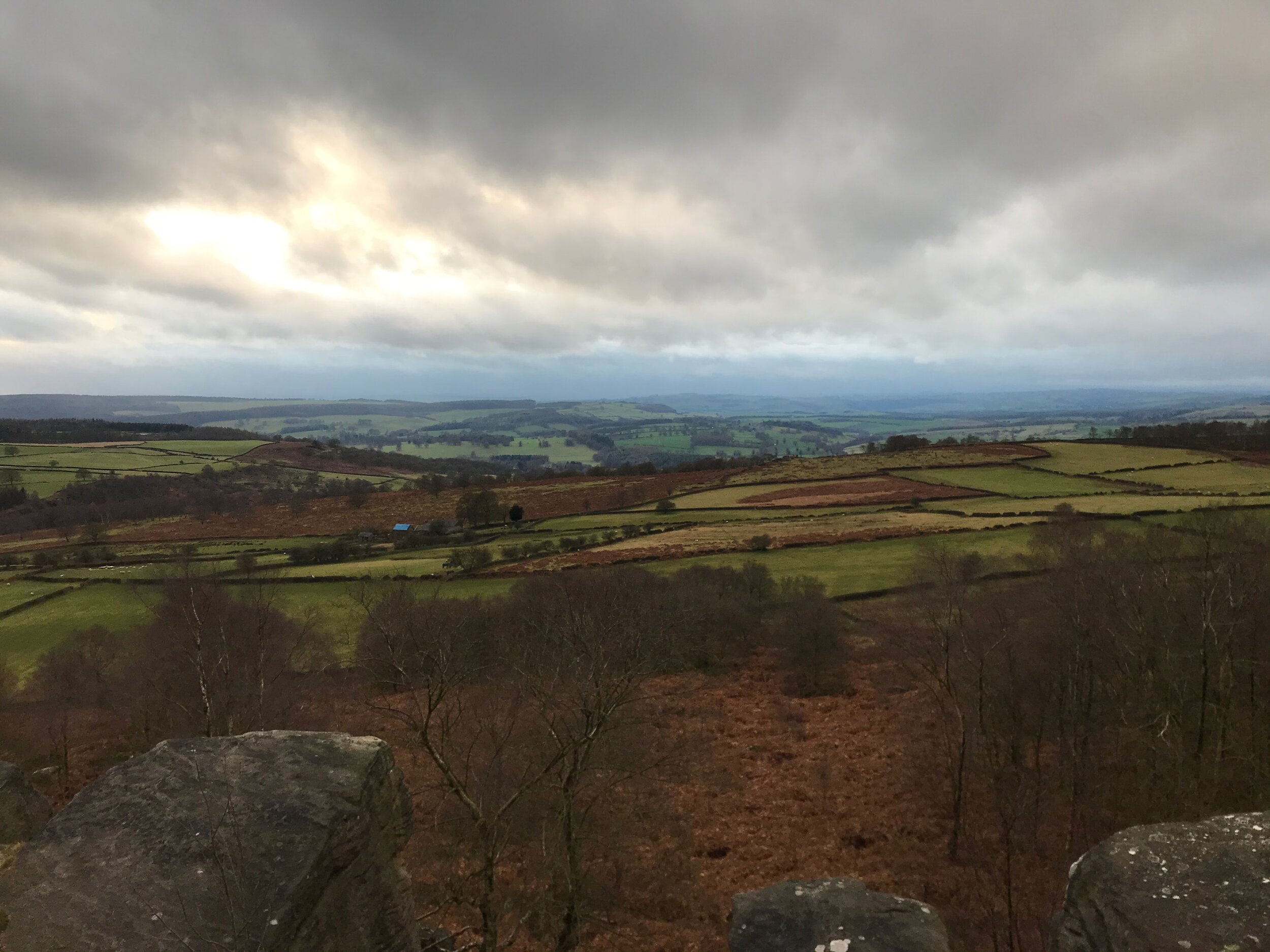

There’s something instantly special about this place. It seems inconceivable that you’re suddenly surrounded by such greenery, so many moss-covered boulders, and where did that cliff face come from? The views from here are beautiful, even on changeable and overcast days.

The Standing Stone

There are said to be around two thousand archaeological features on the plateau that stretches from Gardom’s Edge to Birchen Edge, many dating back to the Neolithic and the Bronze Age. But the most striking examples are located in or very close to the special birch wood on the edge.

The first of these is a triangular Neolithic monolith which stands about two metres high. In 2012, researchers from Nottingham Trent University found evidence that the standing stone had been carefully aligned, angling up towards geographic south, and thereby creating a seasonal sundial.

The standing stone from the West, looking very much like the gnomon of a sundial, with Birchen’s Edge (and the yellow, Winter “savannah”) behind.

In Winter, the sloping north-facing side is in perpetual shadow, and there are only two other examples of 4000-year-old monuments in the British Isles that intentionally use shadows in this way. Both are associated with burial sites (the interplay of light and shadow supposedly represents infinity), but this stone might have other symbolic meanings, and could have been an important marker for Stone Age seasonal gatherings.

Others suggest that in one particular aspect you can see a demonic face, and that the stone may have been chosen as a guardian figure for this very reason. There is something of the Night King about it.

The Carved Rock

About two hundred metres south of the standing stone, there is a slight clearing in the foliage, and here you can find a large, flat carved rock. Its size surprised me both times I visited: the photos I’d seen didn’t prepare me for the scale of the rock the first time I saw it, but on the second visit I was bizarrely shocked by it again. It’s so big that you can find it on Google maps.

The OS map shows the position of the carved rock.

NB. When I use the term ‘rock’, I’m not being very accurate. This isn’t the carved rock that was found in the early 60s. It’s actually a 1996 replica made of fibreglass and polyester resin. It’s surprisingly easy to forget this when you’re looking at it, even though the lichen and moss is less keen to encroach here than on the surrounding rocks, and there’s a distinctively plastic-y crack in it where a hiker has decided to test its strength. If you tap on it, though, it’s a dead giveaway. The original rock was buried for its own protection, though I’ve read conflicting reports about where it is: most think it’s directly below its artificial clone.

On the rock, two ovals almost intersect, and each has exactly ten evenly spaced ‘cups’ inside. Connected to one of these is a classic ‘cup and ring’ marking, featuring a much deeper cup surrounded by two rings. A much smaller cup with a spiral round it nestles between the three larger shapes and a line that I want to call a stem. Further down the rock there are two other cups with more shallow rings, along with other grooves, which may be natural, or perhaps were enhanced by Neolithic tools.

Of course, no one knows what these widespread cup and ring markings mean. It’s easy to reach for the fertility symbol explanation (and from the West, the stone does look quite phallic — see the picture right at the bottom of the blog), but there are other connections between carved rocks: many are placed on land with a view on the way to burial sites on higher ground, perhaps like waymarkers; often, too, the art is carved onto surfaces facing the sky, and may therefore reflect the movements of the celestial objects above.

Meg’s Wall Enclosure

Both the standing stone and the replica carved rock lie just outside a Neolithic enclosure that cordons off a huge portion of the edge. (It’s nicely visualised on this old plan by the University of Sheffield.) Near the edge, there are so many boulders that I worried it would be impossible to see a huge bank of rubble; but in Winter, all the bracken having died back, it’s easy to make out.

Creating the wall would have been a huge undertaking: in places, it’s up to ten metres wide, 1.5 metres high, and altogether it was about 600 metres long, though only earthworks are left at the southern-most end. The effort involved in its creation suggests it was an area of great significance, though the terrain indicates that no one actually settled here. Instead, it’s thought to be an important meeting point, right up to the Bronze Age. Tools found suggest that it could have been a trading place, but such trading may have been part of other ceremonies or feasts. Similar sites in Britain were used for funerary customs, which would seem to tie in with the other archaeological features.

Within the enclosure walls, Gardom’s Edge is at its most lush, full of a staggering array of moss and lichen, including this incredible flowering pixie cup lichen.

Three Men of Gardom’s

Within the ancient enclosure, but with dry stone walls bordering them to the south and east, are three cairns that date back to the 18th Century. Local folklore has it that these were constructed for three shepherds (or lost drunken priests) who died in a storm (or in snow).

This was a burial site long before then, however: the cairns sit atop a Bronze Age barrow (a circular burial mound), though there don’t seem to have been any archaeological studies of the site. Nearby, though, is a partially reconstructed Bronze Age roundhouse, thought to have contained a cremation pit, and cremated remains are known to have been preserved in other barrows.

It seems that Gardom’s Edge can’t be separated from death rituals, and the views from here must have had something to do with its being chosen.

From here, you walk through a gateway in the wall to the south and carry on down the hill. There are more cairns here as the descent becomes steeper and you meet a footpath that takes you to the road, and the pub. From the Robin Hood Inn, you go up the B-road for a short distance, before taking a path to the left, signposted ‘Birchen Edge’. Before long, you come to a steep climb up stair-like rocks, taking you right onto the edge. It’s an easy walk from here.

Alternatively, if you want to see more of the Bronze Age sites on the plateau (like the roundhouse and the aligned pits), you can follow the dry stone wall that runs roughly SW-NE all the way from the Three Men to the roundhouse itself. You can make your way up to Birchen Edge relatively easily from there, if you don’t mind negotiating tall grasses, boggy ground and boulders.

Birchen Edge

Though they are both gritstone edges, the character of Birchen Edge is completely different to Gardom’s. It’s much more like the heather moorland that’s characteristic of the Dark Peak. At the trig point, it’s thirty metres higher than Gardom’s Edge, and the views are incredible.

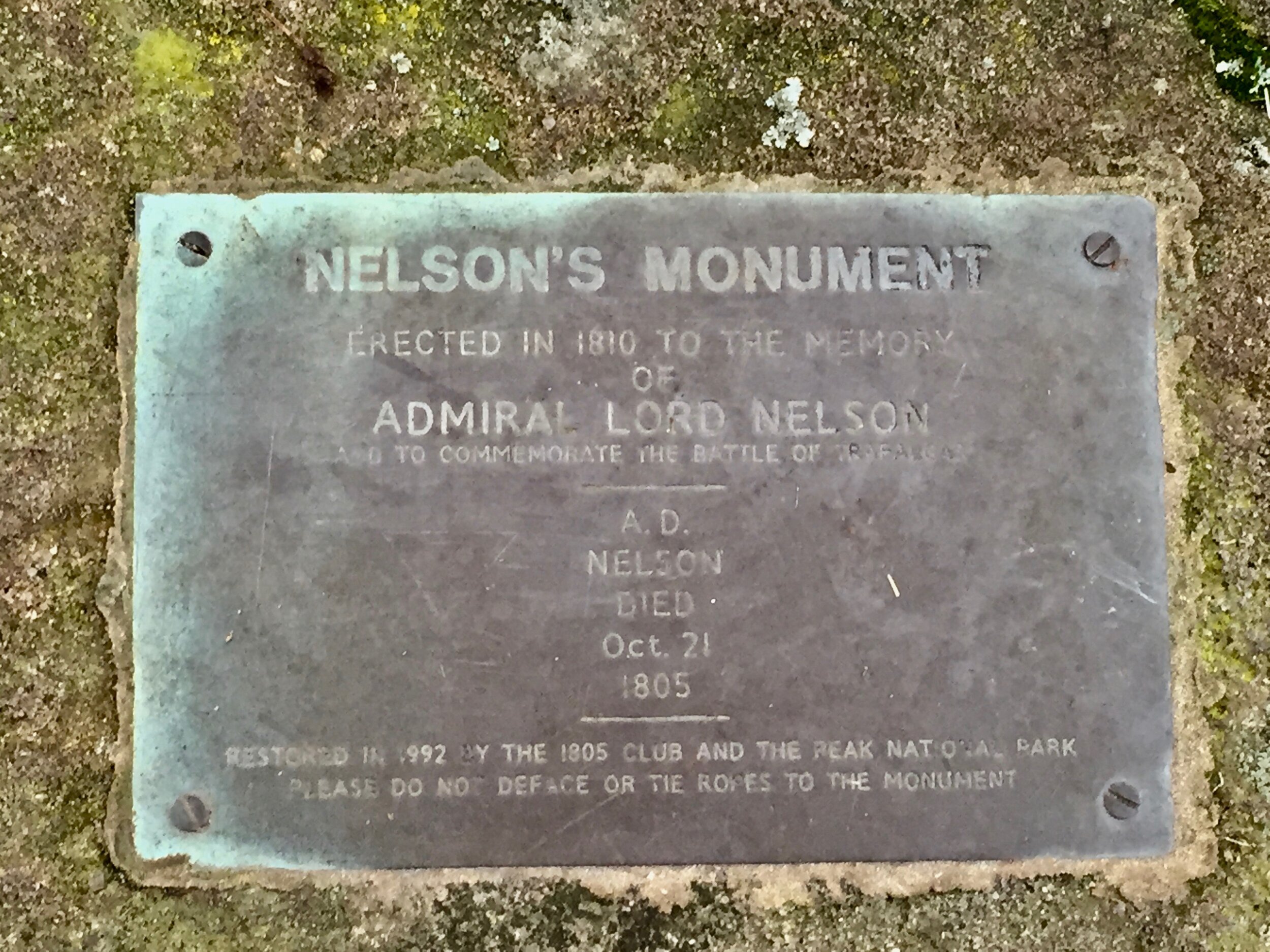

It’s bleaker up here: without trees, the wind whips right into you, and there’s very little by way of interesting features. That’s probably why this edge (and it’s right on the edge) was chosen as the site for a three-metre gritstone obelisk surmounted by a ball. It rather grabs your attention, this monument to Admiral Horatio Nelson, about as far from the sea as you can get in Northern England. There’s something slightly sinister about it, I think: a lonely figure staring out over Derbyshire.

It was erected in 1810, paid for by John Brightman of Baslow, making it one of the first monuments to Nelson, who was killed in 1805. (By contrast, Nelson’s Column wasn’t completed until 1843, though admittedly it’s a little bit taller and more complex, having required a whole square to be built.)

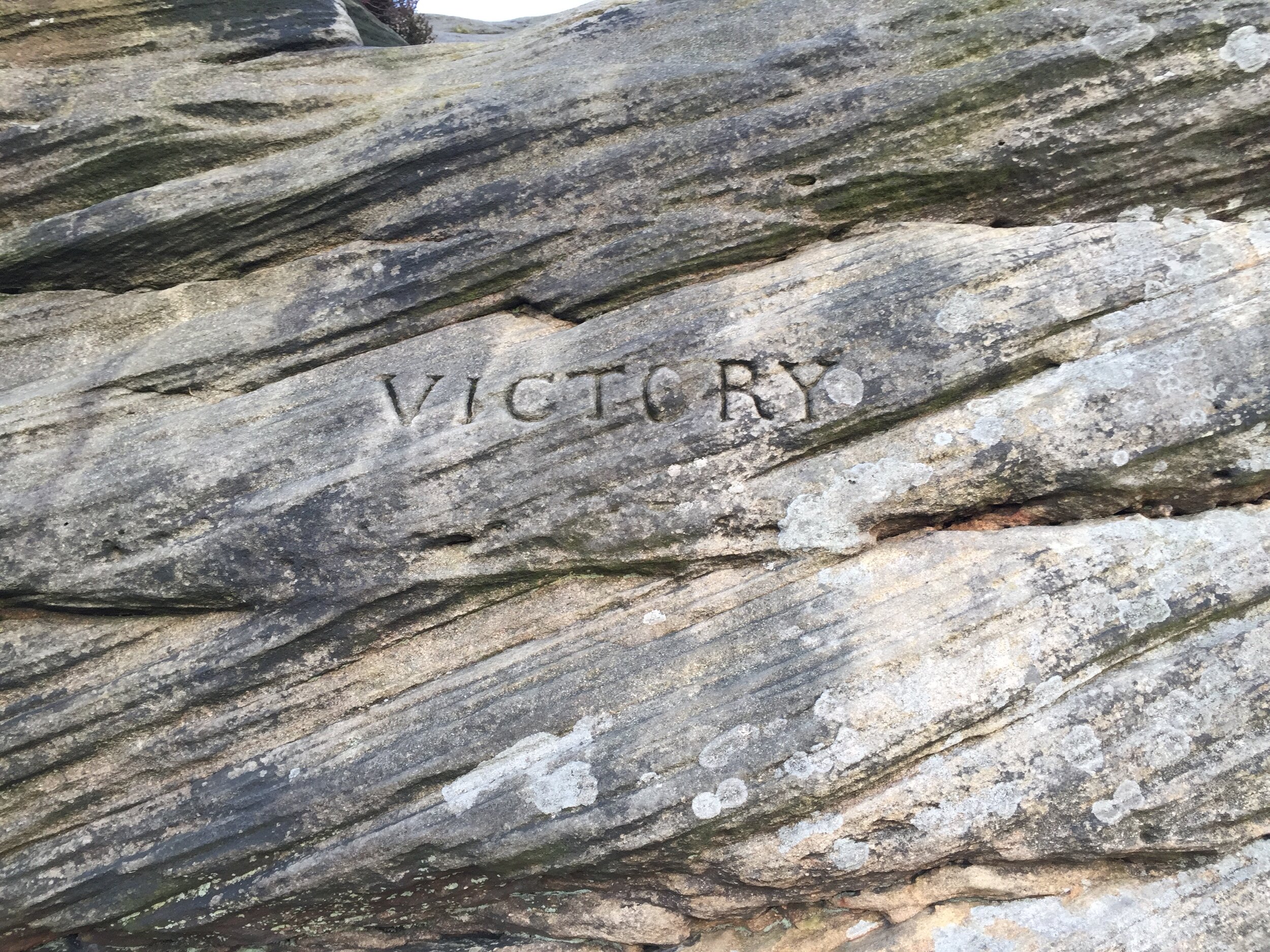

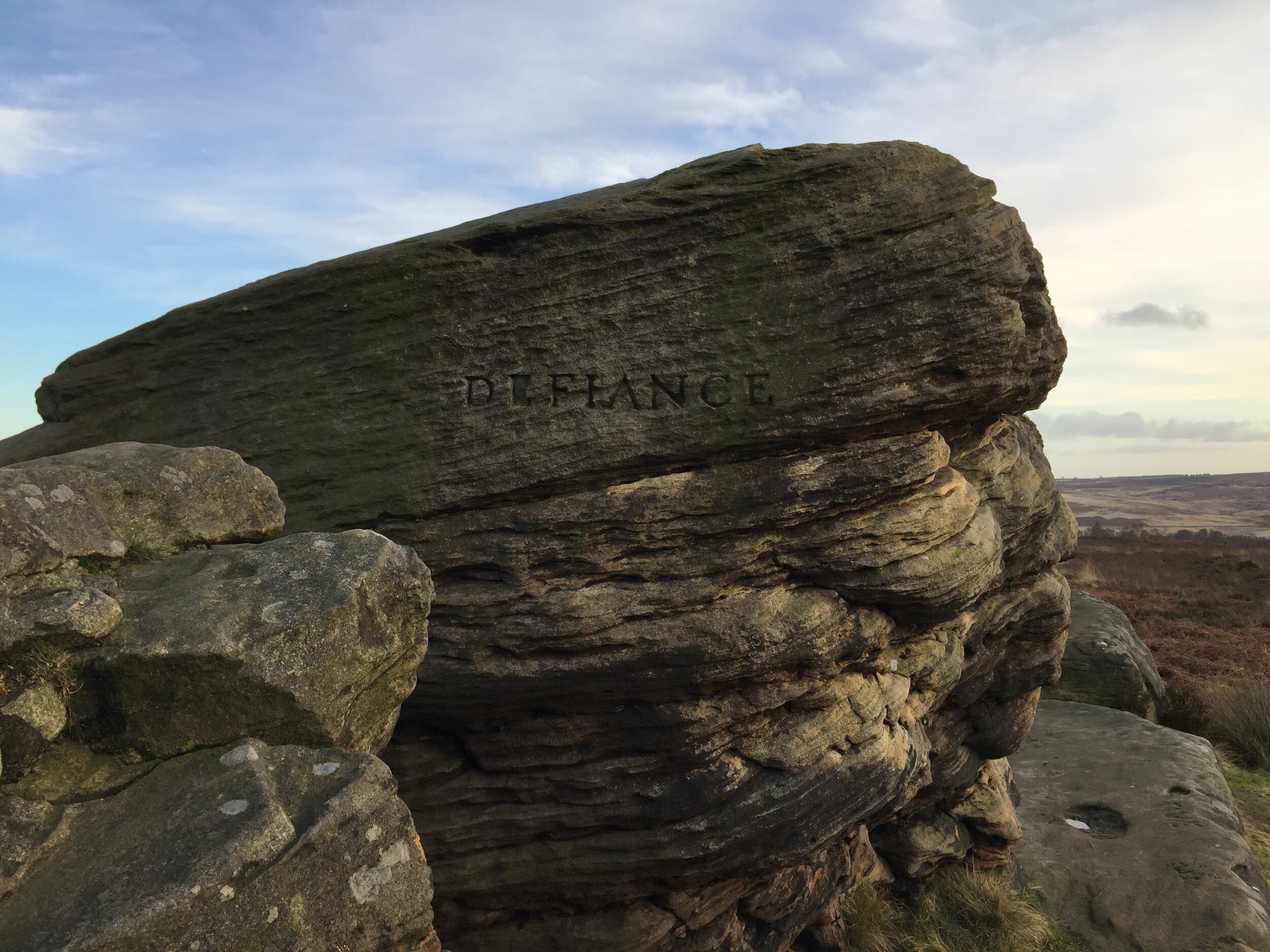

Further back from the edge there are three gritstone outcrops known as the Three Ships, because to some mistaken eyes they resemble the prows of boats. They are no doubt the real reason that the monument was placed here, though I’ve no idea if their name precedes the monument. Each has been inscribed with the name of a warship at the Battle of Trafalgar: from North to South they are Victory (Nelson’s flagship, and the one he died on), Defiance, and “Royal Soverin” (which inexplicably seems to have a semi-colon in the middle of its misspelt name).

From this collection of sites, you continue to head North to the trig point, and then you can take any path you like back down onto the plateau and towards the gate on Clodhall Lane.

![A view of the side of the outcrop named ‘Royal; Soverin’ [sic].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e0dc9494d4c716d3ff361ec/1582218201184-J4M2SHY7S0VYJNJNUP28/IMG_2023.jpg)

![A close-up of the inscription ‘Royal; Soverin’ [sic].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e0dc9494d4c716d3ff361ec/1582218219971-20BWI7JBUAQMIPFDHSJ4/IMG_2022.jpg)

A Brief Tangent on Monuments to Admiral Lord Nelson

I know very little about British naval history or the Napoleonic Wars, but this oddly placed monument to Nelson in the Peaks made me think about how famous and beloved he must have been in Georgian England. I wondered just how many monuments there are to him, and — as far as I can tell — there are fewer than I expected: a mere twenty-two. Actually, the two that were in Ireland were destroyed (a memorial arch in County Cork is said to have been destroyed an impressive three times), leaving twenty. There’s even a monument to Nelson in Bridgetown, Barbados: he spent some time in the Caribbean, marrying his wife there, and evidently making close friends with plantation owners — Nelson was staunchly anti-abolitionist.

Here are the other reminders of Nelson’s prominence in the national (and international) psyche:

There are 199 British street names that make reference to Trafalgar, Nelson’s final, fatal victory.

In 2011, a survey found that there were seventy-eight pubs called ‘Lord Nelson’, thirty-one called ‘Nelson’, five called ‘Admiral Nelson’, five called ‘Nelson’s’, sixteen ‘Trafalgar’s and thirty-two ‘Victory’s.

There’s Admiral Lord Nelson School in Portsmouth.

Nelson Health Centre is a hospital in Merton Park, London.

Nelson’s flagship, HMS Victory, is preserved in Portsmouth.

There are several Nelson Islands, and the city of Nelson in New Zealand is also named for Horatio Nelson.

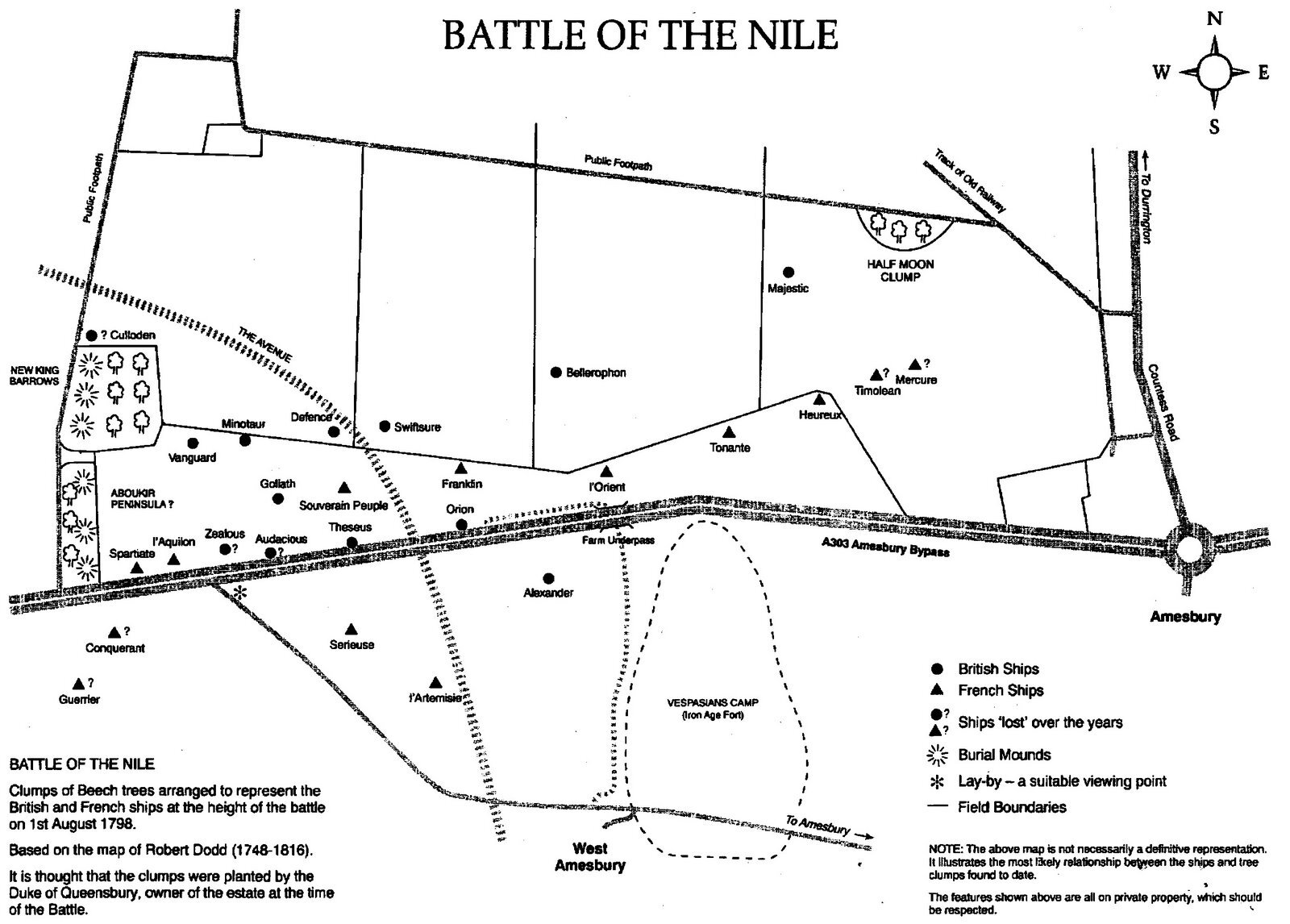

Monuments in Nature

My favourite of the monuments dates from before Nelson’s death: in 1798, the Duke of Queensbury had clumps of trees planted on his land (on Salisbury Plain, a cannon shot away from Stonehenge) to represent the positions of the British and French ships in the Battle of the Nile, where Nelson’s tactics defeated Napoleon. However, the trees planted were beeches, which have a lifespan of 200 years. The clumps that weren’t destroyed to make way for the bypass and which survived into the twenty-first century are now straggly and sickly looking, leading to questions about whether to replant the remaining clumps, or even whether the ‘lost’ clumps should be replaced.

I’m not sure what should be done, if anything, but I see similarities between replanting the clumps with new saplings and replacing ancient artifacts with weatherproof replicas. Is it a disservice to future generations to let objects (or trees) that are hundreds of years old decay naturally? Are visitors to monuments deprived in any way by not being able to access the authentic, original objects?

Whatever the answers, I’ve still got some queries about the decision to bury the ‘real’ carved rock (who is it being preserved for if it’s underground?) and about who got to make that decision on behalf of everyone else.

Links

The Stone Circles website is brilliant, and from the Gardom’s Edge Carved Rock page you’ll find links to the other sites mentioned here, as well as others.

The University of Sheffield Gardom’s Edge page is from the late-90s, and it shows (many of the pages and images don’t exist any more and/or links don’t work), but the information that you can access is great, particularly the interactive plan I link to above.

If you’re into climbing and are thinking of exploring Gardom’s Edge from a different angle to me, then you might like this page. The writer claims that Gardom’s Edge was ‘named after a blacksmith from the Chatsworth Estate’, but I can’t find any other evidence for that, and it seems unlikely in any case. There was a family of Gardoms (related to the blacksmith/ironsmith) who lived in nearby Bubnell Hall though, so there may be a connection.